During the Colonial era, common land was usually held collectively by a town and all persons were entitled to use it for a common use. Land designated in York as common was divided among the inhabitants and became private property.

In 1622 Ferdinandoe Gorges received a land grant from King James I of England. The area was called the province of Maine. Gorges saw his Charter as an opportunity for wealth. His dominion began as a real estate business that has never ended. One of the most compelling incentives to coax those from England to settle in the colonies was the idea that if they decided to come, they could own land that could be passed down generationally, unlike anything offered in England to common people. This provided assurance for better security in old age, among other considerations. All improvements to the land would enhance the value–helping to create generational wealth.

Individual land grants were utilized throughout the Colonial period. Many examples can be found in Clerk’s Book, Volume I and II, viewable at the town clerk’s office. Most of these grants were were intended to provide settlers with enough land to build a home and support a family. There were many ways to make a living though agriculture was the most popular. Other ways were fishing, preaching or one could become a millwright, cordwainer, a tanner of leather, carpenter, a shipwright, and so forth. Most occupations, like farming, for example, required adequate local resources such as fertilizer in the form of seaweed, and sawmills required timber.

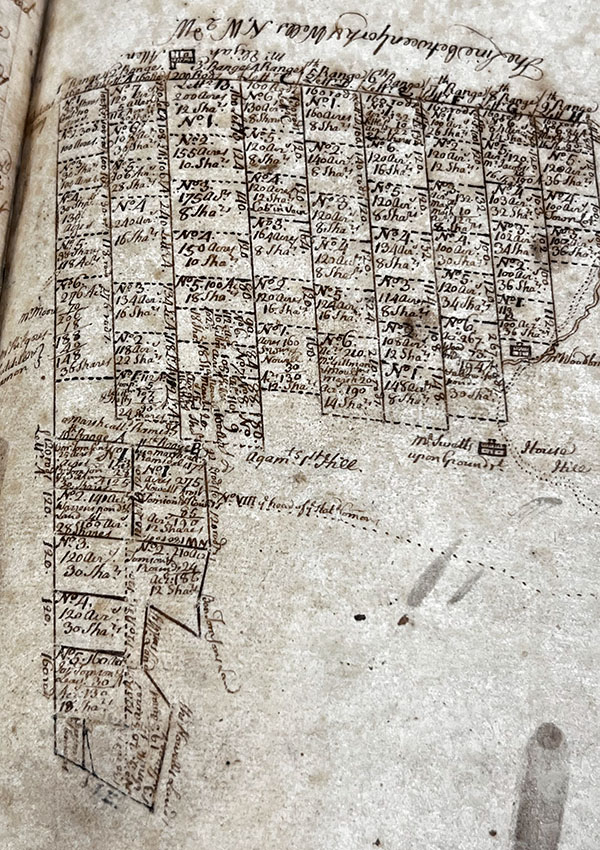

The turbulence of the 17th century slowly waned and during the early 18th century York was established as a Town with an organized government. The Town set a goal of community expansion as a foremost mission. Within the town boundaries there was abundant land for the taking. In 1732, an official Committee was created to fairly divide and distribute land that was considered too be beneficial for capitalizing on York’s natural resources. Surveyors divided the land into rectangles and those interested could apply for a grant. There was a nominal fee for administration but otherwise residents were entitled to participate.

Those who had been here for multiple generations and established themselves on the higher social levels received up to eight shares of each division. Those who had more recently settled were less likely to be so fortunate and would more likely be granted one to six shares. These shares were in addition to what settlers had already acquired, including grants on which they built their homes. The distribution of shares was an ongoing process as can be seen in the Book of the Proprietors. Typically, recipients were grouped together within a range and lot that they had drawn from a hat. Several people, depending on entitlement and the number of shares in a lot would collectively work out the individual boundries among themselves and report the results to the Proprietors for finalization. We can see that newly acquired lots were sold by some not long after acquiring them.

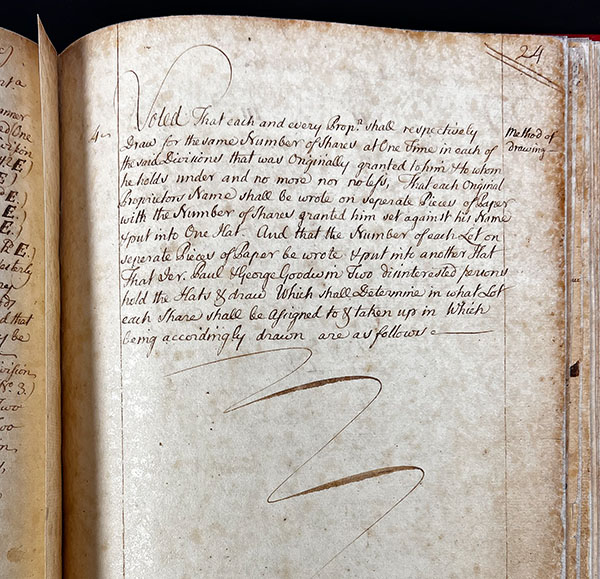

In the above page from the Book of Proprietors, we can see the method used for distributing property.

Submitted by Kevin Freeman