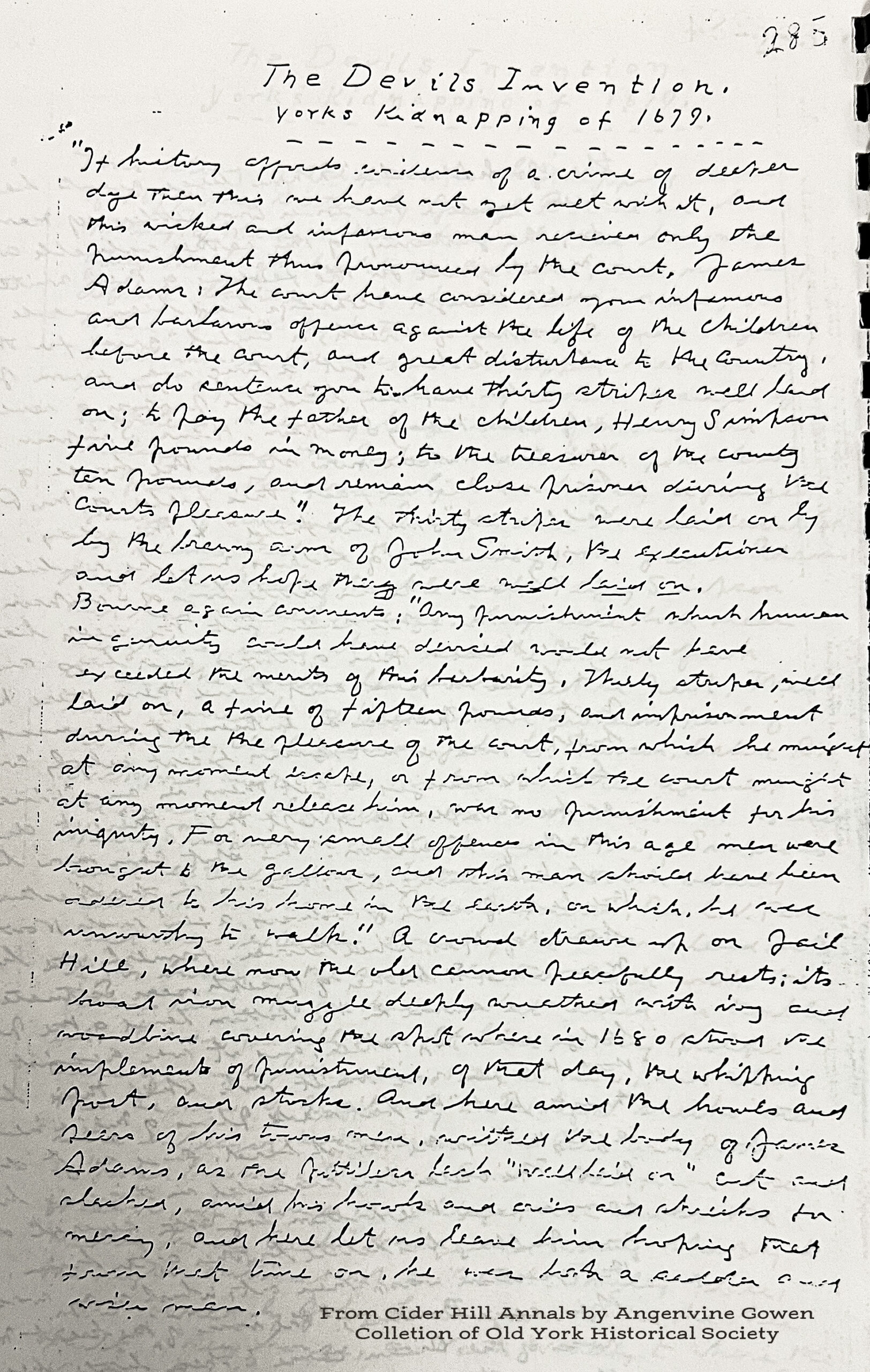

This is the tragic story of a kidnapping in Colonial York, Maine. The below can be found in Cider Hill Annals and Miscellaneous Sketches, by Angevine W. Gowen. He hand wrote what appears to be a court document. The source of this document is currently unknown. A copy of Gowen’s book can be seen at Old York Historical Society’s Archive.

Several members of York History Group joined together to transcribe the above account, as follows…

“If history affords evidence of a crime of deeper [dye?] than this we have not yet met with it, and this wicked and infamous man receives only the punishment thus summoned by the court. James Adams: the court has considered your infamous and barbarous offenses against the life of the children before the court, and great disturbance to the county, and so sentences you to have thirty stripes well laid on; £ pay the father of the children, Henry Simpson, five pounds in money; to the treasurer of the county ten pounds, and remain close prisoner during the courts pleasure.” The thirty stripes were laid on by the brawny arm of John Smith, the executioner and let us hope they were well laid on. Bourne again comments: “Any punishment which human ingenuity could have devised would not have exceeded the merits of this barbarity, thirty stripes, well laid on, a fine of fifteen pounds, and imprisonment, during the pleasure of the court, from which he might at any moment escape, or from which the court might at any moment release him, were no punishment for his iniquity. For very small offences in this age men were brought to the gallows, and this man should have been added to his home in the earth, on which, he was unworthy to walk.” A crowd draws up on Jail Hill, where now the old common peacefully rests, its broad [?] [?] deeply wreathed with ivy and woodline covering the spot where in 1680 stood its implements of punishment, of that day, the whipping past, and stocks. And here amid the howls and jeers of his townsmen, withers the body of James Adams, as the [?] lash “well laid on” out and stacked, amid his howls and cries and shrieks for mercy, and here let us leave him hoping that from that time on, he was both a sadder and wiser man.”

Thanks to Juanita Trafton Reed, Kathy Cawrse, Racheal Bottino, Danny Bottino, Joanne Weiss Curran, for assisting with this transcription. Juanita commented on the Facebook post…My transposition matches most of what you have here (above), with these few exceptions… I believe it is “strikes” not stripes./ Whipping post. (instead of “past”) Instead of common — I think it is “cannon”. / lash “well laid on” cut and slashed ( rather than cut and stacked) and where you have the £ sign I read it as “to”…”to the father”

York in American History: Fate of Ensign Henry Simpson

Notes: During the late 17th Century, life in early colonial York was daunting, short, often brutish, terrifying and unpredictable. Based on research from original documents, such as court records, James Kences paints just such a portrait in this essay.

This story is published on Seacoast Online and provides additional information on the Simpson Family of York.

By James Kences

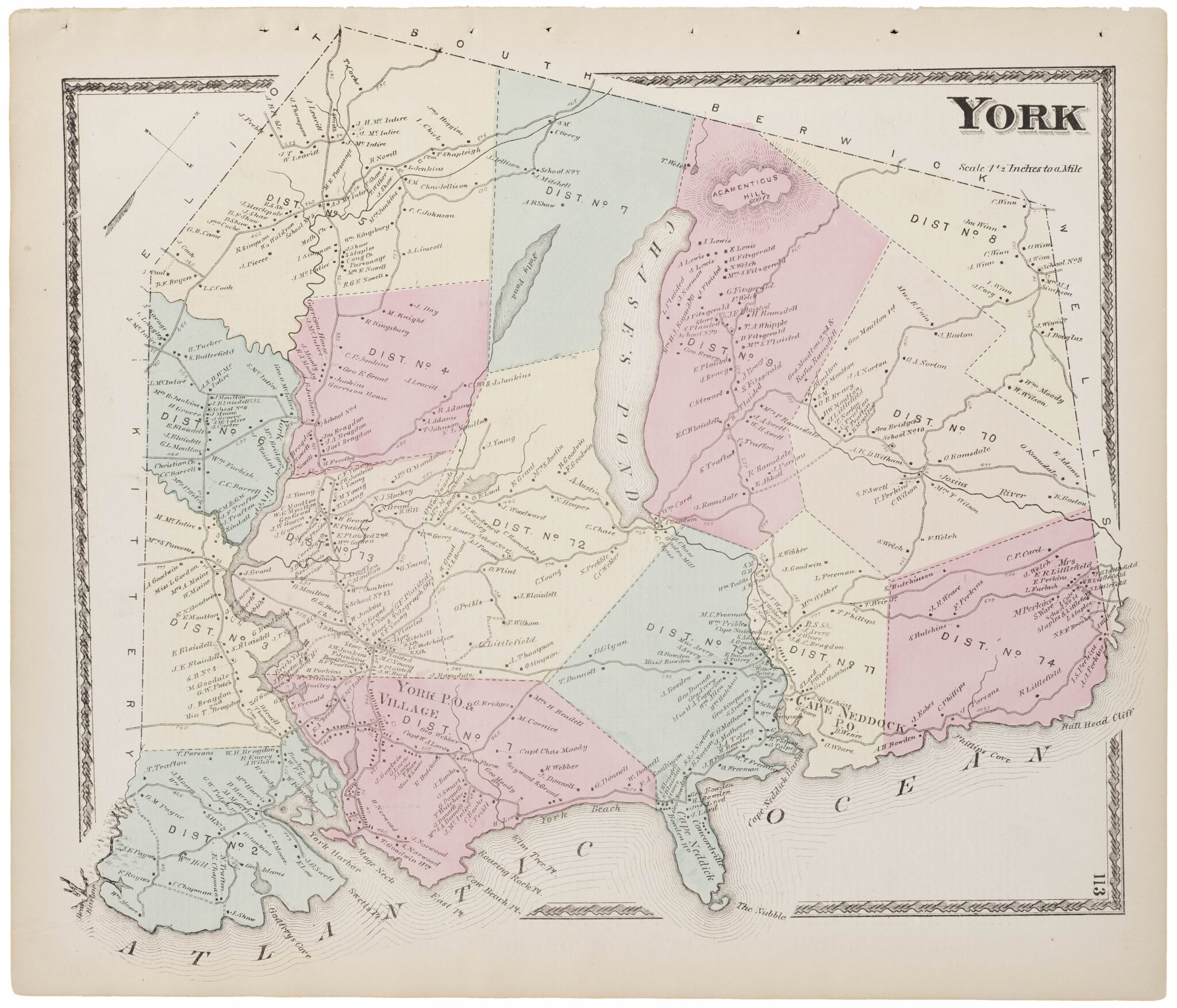

One of the final events in the life of Ensign Henry Simpson was his participation at a court of sessions of the peace on Dec. 29, 1691. Within a month, he would be among the victims of a Native American raid upon the town. Simpson and his wife were presumed to have been killed, and two of their sons, Henry and Jabez, were taken into captivity.

Simpson was married to Abigail Moulton, sister to Joseph Moulton, who on the day of the attack also perished with his wife. Their son Joseph was captured. Jeremiah Moulton, who was only three or four years of age in 1692, was to become one of the military and political leaders of 18th Century York.

The reconstructed list of casualties from the raid, included in total number, three other married couples: in addition to Simpson and Moulton, Nathaniel Masterson and his wife, Elizabeth; Philip Cooper, and his wife, Anne; Thomas Paine and his wife, Elizabeth. In each of the three instances, some of their children were taken prisoners and accompanied the raiding party upon its return to Canada

And what of the fates of those children? Masterson’s daughter Abiel, Mary Cooper, and Bethiah Paine, eventually returned, but only after a period of years. Mary Cooper was redeemed in 1695, together with Henry Simpson and seven other persons. Three years later, Bethia Paine was brought back. A decade had passed, Jabez Simpson was apparently still inside French Canada.

The documentary sources are quite spare, and often only names have survived, but with effort a deeper dimension to the slight details is possible. Ensign Henry Simpson can be profiled more richly than the others. The story begins with his childhood. He was about four when his father, afflicted by illness drafted his will in March of 1647. An only child at the time, a portion of the estate was apportioned to him.

Shortly after his father’s death in the summer of 1648, Simpson’s mother remarried, and became the wife of Nicholas Bond. In May of 1650, Henry Simpson, only six years old, testified at the trial of Robert Collins, who was charged with assault upon his mother. The man he knew as “fat Robert,” had attacked her at night inside their house.

“She being in her house, her children in bed, she was making a cake for them against the next day to leave them,” she recounted at the trial. It was midnight, and she required some firewood, and was at the door when Collins forced his way in. The testimony is somewhat confusing, but it described multiple incidents that involved Collins. In one confrontation, she declared to him, “leave my company and meddle not with me, if not I will make you a shame to all New England!”

Jane Bond acknowledged, “she could not save herself,” her husband at the moment, was absent “to the East.” The jury found Collins guilty of the crime. He was “to receive forty stripes save one, and fined ten pounds,” as punishment. As a glimpse into life here in the early period, the trial is of considerable value. The five witnesses had included Henry Norton, who was not only a close neighbor, but also a relative. Norton had heard Henry Simpson’s mother call for him, “Cousin Norton!” “Cousin Norton!” but he failed to respond.

The Norton family were prominent and well connected. Henry Simpson’s grandfather was the veteran soldier Walter Norton who was killed by the Native Americans in Connecticut in 1634. His grandmother upon his death married William Hooke, who belonged to a family of merchants at Bristol, a city in the southwest of England. This town for a brief period was named Bristol, and the influence of the Hookes was expressed through the choice of the name.

Henry Simpson could claim high social standing as kindred to the two families. He was elected to various town offices, constable, and served as a selectman. He held a military rank, and was frequently a member of juries, and as mentioned, was part of the grand jury only weeks before the raid in 1692.

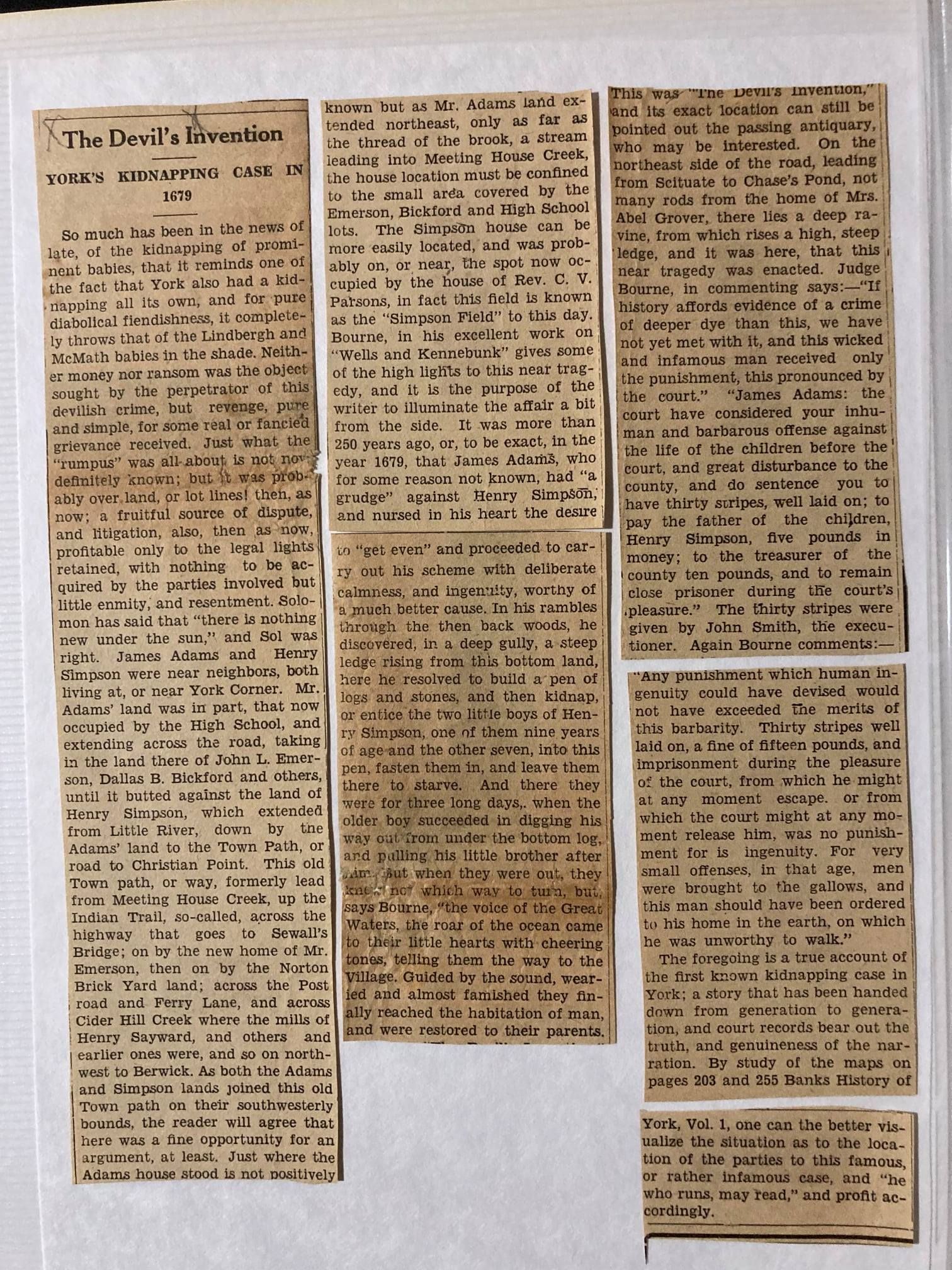

Whatever provoked James Adams to kidnap and imprison Simpson’s children inside an improvised enclosure that was to be known henceforth as “The Devil’s Invention,” is unfortunately lost to history. But the record has survived for the court session of July 1679. For the “barbarous offense against the life of the children,” Adams received a sentence of a severe whipping, “thirty stripes well laid on,” and was also to pay Simpson, “the father of the said children,” five pounds in damages.

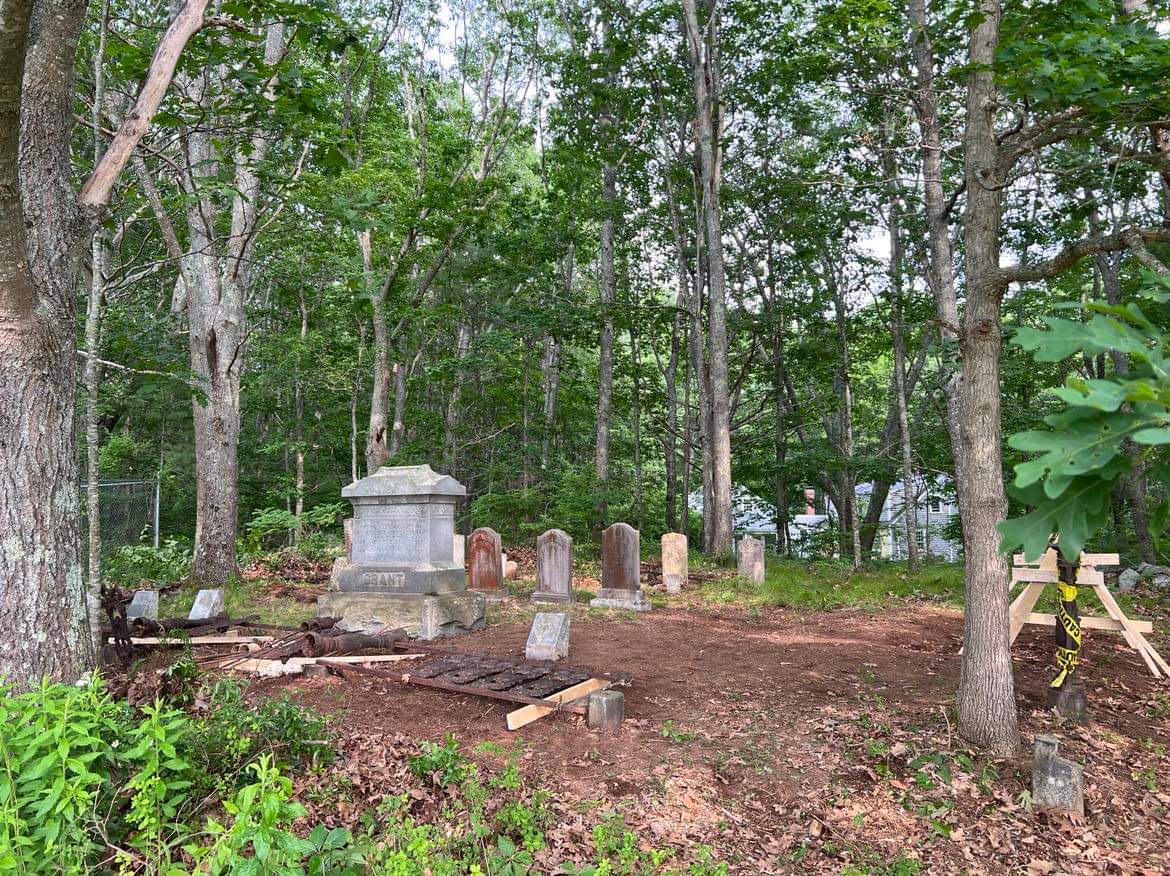

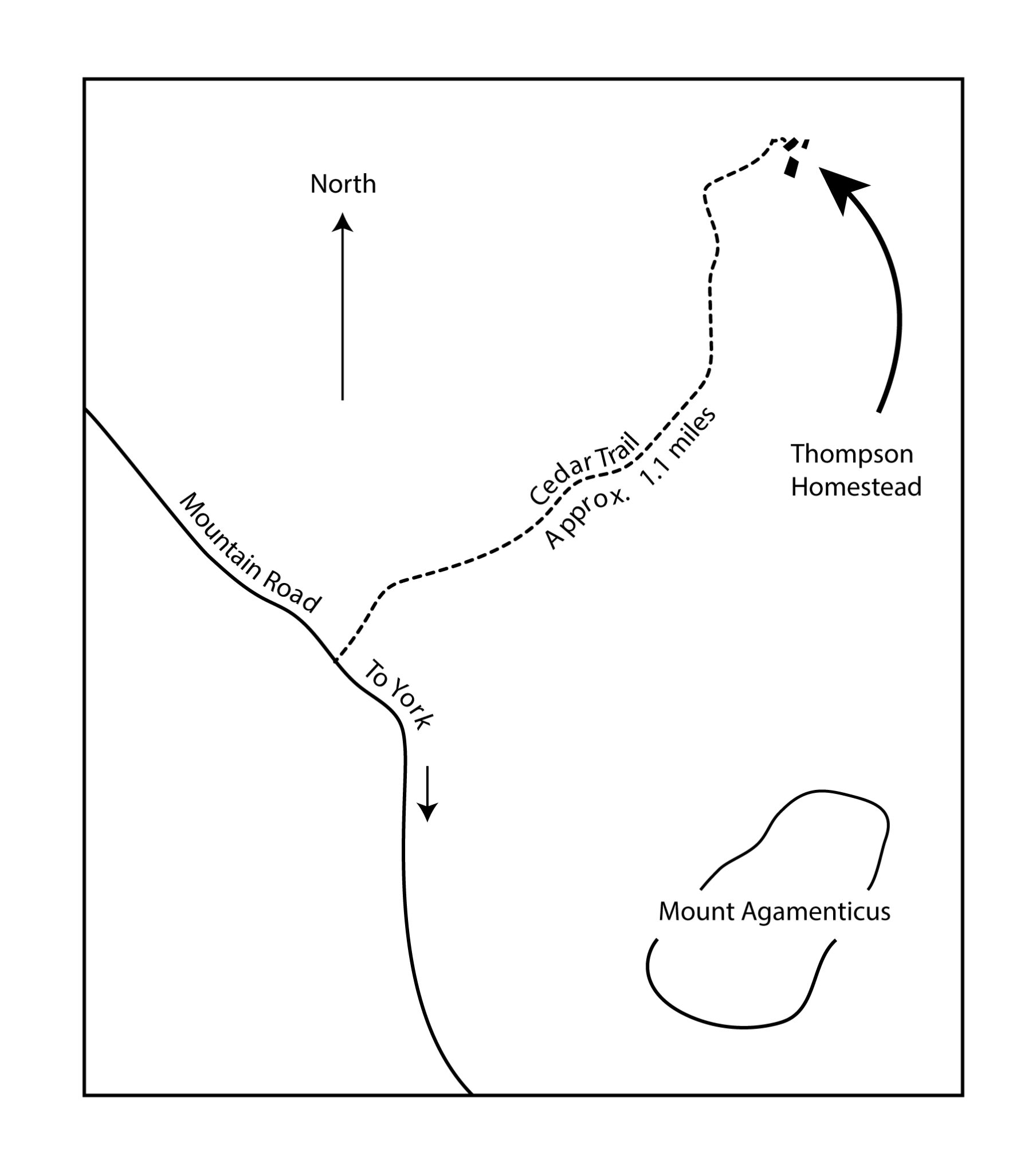

The site of the notorious structure, was according to Charles Banks, “in the region of Scituate, easterly from the main highway through that settlement.” Philip and Nathaniel Adams, the father and brother of James, appear to have been among the victims of the 1692 raid.