Prepared for the York History Group by Tom Prince

November 11, 2022

Watch Tom’s presentation, in three parts on YouTube…

Civilian Activity and Volunteer Services In York, Maine during World War II

The United States was thrust into the realization of a possible world conflict when Nazi Germany took hostile action against Poland with the invasion of that country on September 1, 1939. This led to a declaration of war by Great Britain and France against Germany on September 3, 1939 which was considered the beginning of World War II. In 1940 the war in Europe quickly escalated with the fall of France to Germany, Germany’s annexation of several European countries, and Germany’s continuous bombing of London and other major cities in Great Britain. Throughout 1940 Japan’s desire to dominate the Asia Pacific region led to increased concerns of a worldwide conflict. On September 27, 1940 Japan, Germany and Italy signed the Tripartite Pact to unify their promise to protect one another against the threat of the U.S. entering the war, thus solidifying the “Axis Coalition.”

Throughout 1940, the U.S. remained neutral as many of its citizens and politicians had no desire to bring war to America’s mainland nor involve its citizens in fighting in European and Pacific regions. However, by this point in time, many US citizens came to the conclusion war was on America’s doorstep.

Back home in Southern Maine and Seacoast NH, the Portsmouth Herald kept everyone well apprised of the escalation of war in Europe and across the Atlantic Ocean. German U-boats were now torpedoing merchant shipping in the Atlantic destined for Great Britain. Some of these attacks were close to US shores particularly in the mid-Atlantic region. And with Germany’s past track record of nighttime bombings of Great Britain cities there was a growing concern among U.S. citizens of an elevated threat of a German air attack upon the shores of the northeastern U.S. Locally, the threat against the Portsmouth Naval Shipyard seemed real and very possible.

By now, U.S. military efforts to prepare a defense against hostile attacks were underway. In Portsmouth, NH and Kittery, Maine the U.S. Army Coast Artillery was activated in February 1940 to protect the mouth of the Piscataqua River with mines and by developing aggressive plans to upgrade coastal forts and artillery defenses at the mouth of the river. The heart of the Portsmouth harbor defense system would be a new battery of two 16 inch guns at Fort Dearborn in Rye, NH with a range of 25 miles capable of countering possible German naval threats. Government orders were issued and funded by Congress for the construction of additional Navy submarines and associated infrastructure at the Navy Yard. In the fall of 1940 Congress passed a law requiring all males between 21 and 35 to sign up for the first peace-time draft in the nation’s history.

It was evident war was getting closer and closer to America.

On March 11, 1941 the Lend-Lease Act was enacted. This was an agreement whereby the US would supply Great Britain and other Allied countries with food, oil, warships, warplanes and other weaponry. Locally, in the summer of 1941 under this agreement, three British submarines were overhauled at the Shipyard. Local families took in British sailors as boarders while their submarines were out of commission. My grandparents in Kittery were one example of a family which took in a British sailor for six months. Other families across the Seacoast, including in York, offered British sailors living accommodations while their submarines were overhauled at the Yard.

The Office of Civilian Defense (OCD) was established by President Roosevelt in May 1941. Initially it was responsible for planning community health programs and medical care of civilians in the event of a military attack on the United States. Civilian Defense (after the War called Civil Defense) quickly developed into a U.S. nationwide civilian volunteer organization whose primary purpose was the prevention, detection and survival from an enemy air attack. Ask any civilian who lived through World War II; their most vivid memories were air raid warnings, blackout drills, and neighborhood wardens with armbands patrolling their assigned streets. These all fell under the umbrella of Civilian Defense.

By the end of the summer of 1941, most seacoast Maine and New Hampshire citizens considered a German air attack highly probable. Fear of enemy attack was now heightened in the minds of the citizens in York and surrounding towns.

In the fall of 1941 (before the attack on Pearl Harbor) the citizens of York decided to get out ahead of the curve by mobilizing civilian volunteers groups using recommendations and structure as outlined by the Civilian Defense. Of all towns in the local area, York citizens were the most eager to initiate action to protect and safeguard its citizens against possible enemy attacks.

York citizens organized a town-wide drill for November 11, 1941 to show evidence of preparation for an emergency. Numerous citizens organized several sub committees including Home Guard, plane spotting, disaster relief, law and order, rescue and labor, medical aid, food supply, and transportation.

The committees and the names of York volunteers who comprised committee memberships were outlined in the following Portsmouth Herald feature article on October 17, 1941.

Thus, on November 11, 1941, York, Maine had what was recorded as America’s first bombing drill. Following is the Portsmouth Herald’s full account of the drill as published on the following day.

As a side note, that was 81 years ago from the date of this paper of November 11, 2022 on Civilian activities during World War II.

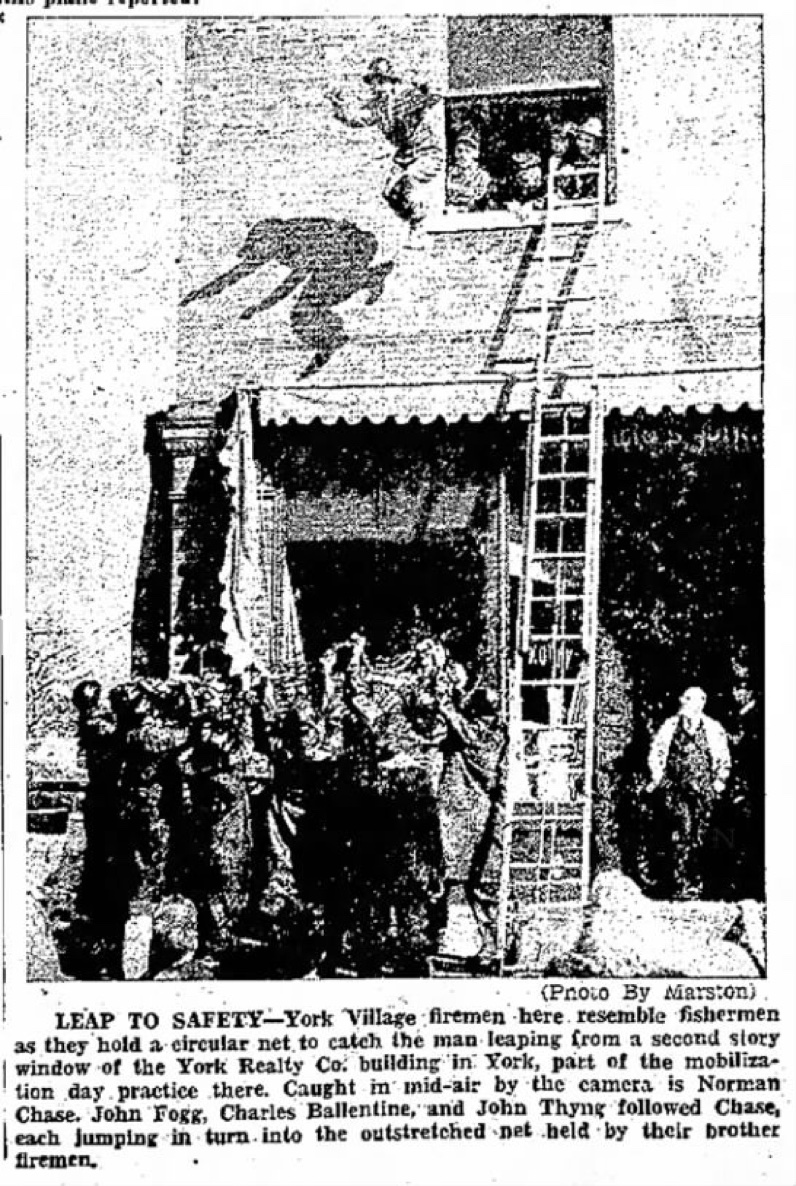

Below is an original photo of one of the York Village firemen leaping to safety from the York Realty Co. building during the drill on November 11, 1941.

A month after York’s mobilization and successful first bombing drill under the Office of Civilian Defense, Japan struck a secret, devastating air attack upon US military forces at Pearl Harbor in Hawaii on December 7, 1941. The next day, December 8, the US declared war on Japan. In turn Germany and Italy declared war on the United States. This prompted the US Congress to declare war on Germany on December 11, 1941. The United States had now officially entered World War II. It’s fortunate York, Maine had done its homework a month earlier and was now ready to safeguard its citizens and do its part to provide for the protection of the country.

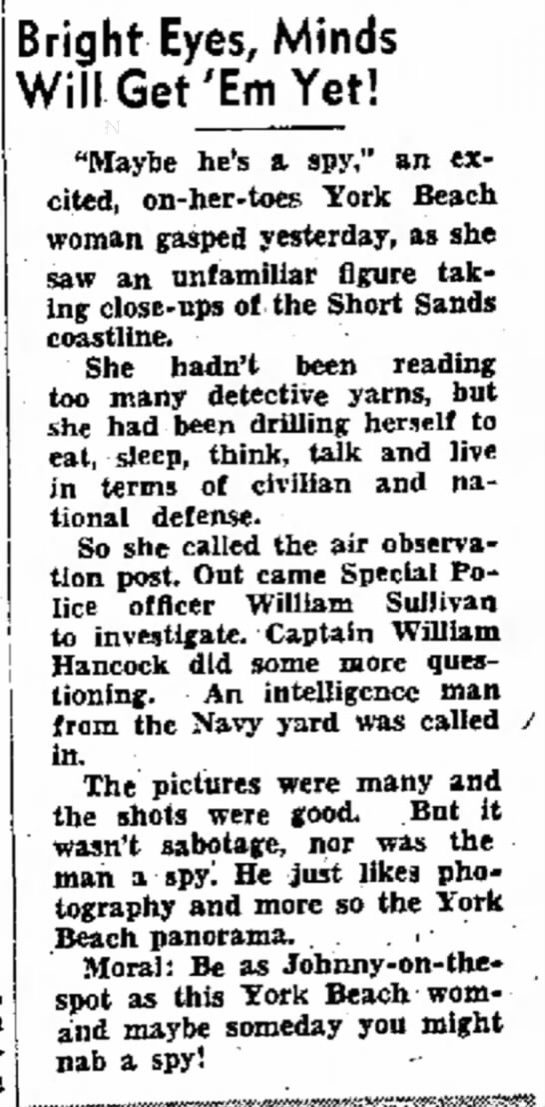

Spy at Short Sands

Just a week after the attack on Pearl Harbor and a few days after the US declared war on Japan and Germany, the citizens of York were understandably at a heightened level of concern and watch. According to a newspaper report in the Portsmouth Herald on December 16, 1941, one York Beach woman took her concern perhaps too seriously. The good news for York, this was a false alarm. Below is the report.

The Civilian Defense Structure

After Pearl Harbor and the declarations of war by the United States against Japan and Germany, military mobilization of the various branches of the U.S. armed forces immediately followed. It is not the intent of this paper to discuss the country’s overseas military initiatives; rather the topics to be discussed are the mandatory and volunteer actions of ordinary citizens here in York and across America in contributing to the war effort.

These actions all fell under the country’s Civilian Defense Organization. As mentioned earlier, this organization had its beginning after formation in May 1941 as the Office of Civilian Defense (OCD.) By January, 1942 the OCD formed the United States Defense Corps to recruit and train volunteers on measures to protect civilians in a war related emergency.

Civilian Defense was a nationwide civilian initiative under the direction of the U.S. Army. Locally, in the Town of York, its citizens were assigned to the Portsmouth Defense Area which was integrated with the Portsmouth Harbor Defense System. The seacoast area of southern Maine and seacoast New Hampshire were governed by the Portsmouth Council of Defense which was staffed 24 hours a day from December 9, 1941 until February 22, 1944. The OCD and the Portsmouth Council governed two primary segments: homeland defense and service.

Homeland Defense was under the Defense Corps. Under this group, citizens staffed observation towers, patrolled neighborhoods, enforced dim-out requirements, conducted blackout drills and planned support for citizens in the event of bombing attacks like those that decimated Great Britain.

The Service Corps had responsibilities for coordinating consumer affairs, housing availability, food and nutrition, medical, salvage drives, the sale of war bonds and interfacing with the Red Cross.

Membership qualifications in either the defense or service corps were, “all able-bodied, responsible persons in the community – men, women, housewives, laborers, business and professional people, boys and girls and the elderly.”

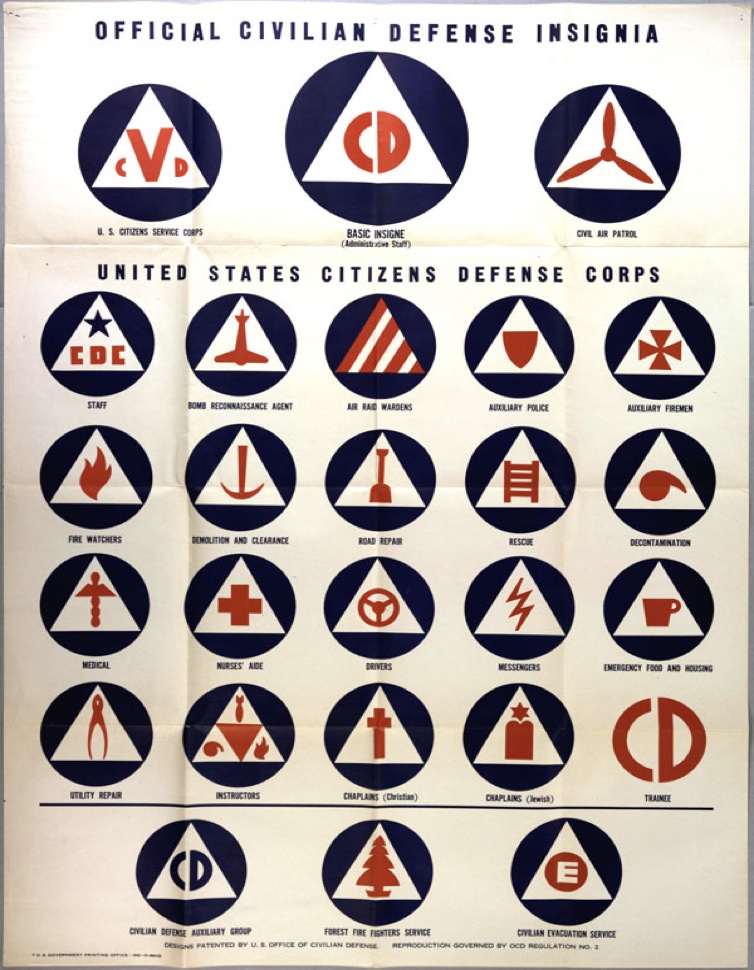

The insignia in the poster featured below, published in 1942, illustrate the numerous jobs assigned to civilian volunteers. Enrolled and trained volunteers displayed their insignia on arm bands and on uniforms or civilian dress.

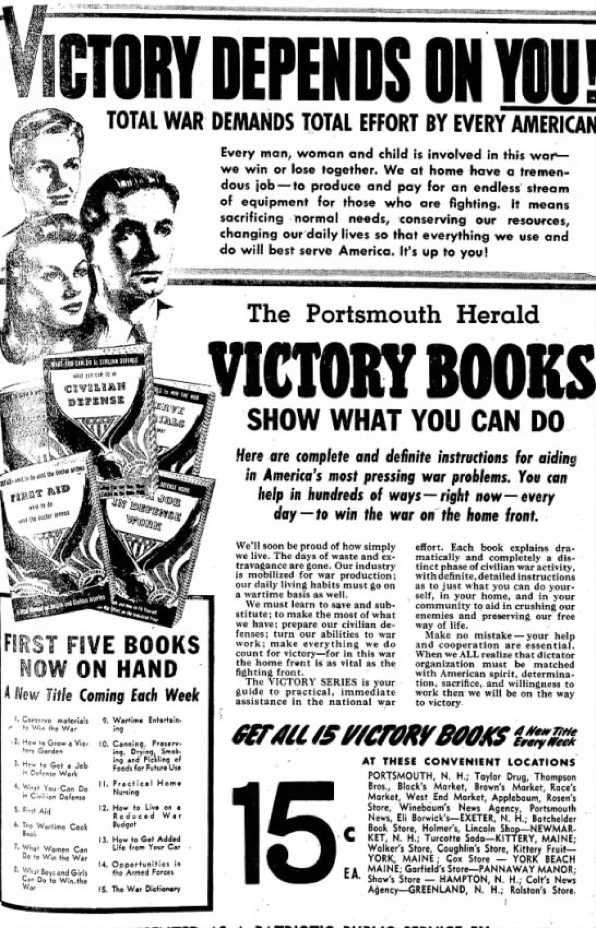

To assist citizens to better understand the various initiates available for participation, a series of “Victory Books” were published starting early in 1942. Among the retail stores and newsstands, the books were sold at Cox Store in York Village and at Garfield’s Store in York Beach.

The first five books available early in the publication series included the following titles:

“Conserve Materials to Win the War”

“How to Grow a Victory Garden”

“How to Get a Job in Defense Work”

“What You Can Do in Civilian Defense”

“First Aid”

These books stressed the importance of all citizens working together for the war effort. This same or similar message was delivered continuously to American citizens during the first two years of the war 1942-1943. The message….

“Every man, woman and child is involved in this war – we will win or lose together. We at home have a tremendous job – to produce and pay for an endless stream of equipment for those who are fighting. It means sacrificing normal needs, conserving our resources, changing our daily lives so that everything we use and do will best serve America. It’s up to you!”

Aircraft Warning Service

The following is the back story of York’s Aircraft Observation Service which was the foundation of the Civilian Defense Corp Air Raid Warning Service. At first the post’s focus was on aircraft, but soon was extended to ships upon the ocean.

In the spring of 1941, Dr. David Harriman as commander of the Edward Ramsdell Post, American Legion, was appointed observation post organizer and at that time called together a group to form a York Observation Post. Of note, many in this group of original members remained active in aircraft and ship observation throughout the war.

At this point in 1941, John Breckinridge was appointed the Chief Observer with Ralph Hawkes and Cato Philbrick assistant. Upon the death of Mr. Breckinridge in the summer of 1941, Mr. Guy Messenger was appointed chief observer. A small building on the estate of Mrs. J.G.M. Stone at York Harbor was loaned to the Post. The location of this building was on a high point of land off Roaring Rock Road.

By the end of the summer of 1941 with World War II underway in Europe, these men formed this volunteer group with the mission to watch for German aircraft and enemy ships that may be approaching the shores of southern Maine. We first read about this group’s initial achievement in the newspaper account of York’s first air raid drill held on November 11, 1941 which noted, “Men at the Roaring Rock air observation post who spotted the bombing squadron gave the signal which spurred defense workers to action.”

The morning after Japan’s air attack on Pearl Harbor, Mr. Messenger was notified by Army Corp headquarters to upgrade the post machinery to full time operation. Within two hours the first men were at their post and the set-up was working smoothly. From that moment on the Observation Post never ceased its vigilance throughout the critical years of World War II from December 1941 – December 1943.

During the first winter (1941-1942) those on watch took turns standing outside the building in all kinds of weather. In the summer of 1942 an observation tower was built nearly all from volunteer labor. The observation tower contained a wood stove in the main room with an enclosed observation area high on the tower. High powered field glasses were donated by Harold C. Richards.

York was not alone in establishing sites with volunteers for enemy aircraft observation. In New Hampshire there were 195 observation posts throughout the state; closer to the seacoast many towns had more than one post. In the State of Maine there were a total of 30,000 volunteers in the Aircraft Warning Service. In York, it was decided one post was adequate because of its location with a commanding view of the sky, ocean and shoreline.

Training for the volunteers at first involved memorizing the silhouetted shapes of airplanes and ships using flash cards. An observer reported every passing aircraft or vessel, regardless of size, shape, or description and then telephoned the information to the Portsmouth Regional Center where the movement of specific craft could be tracked on a map.

Aircraft identification quickly became something of a fad for adults and children. Nationally, toy kits such as “Plane Spotter” were sold. Advertisements cited Parker Brother’s Warplane Game and Spotting became popular. Playing cards from Bicycle decks featured different profiles of German planes. Playing cards enclosed with bubble gum had planes identified belonging to Germany or Japan.

More formal training was conducted by the Army for the York Observation Post in March 1943 when Philip Marston was appointed recognition officer and sent to an Army school in Boston to learn and then teach others how to recognize planes by make and type. Upon his return from the schooling, Marston conducted classes for other observers at the post.

Throughout the war years the York Observation Post kept putting out requests seeking additional volunteers who could give two hours, once or twice a week. During its last year of operation, the Post’s regular volunteers were augmented with students from the High School. Apparently the Post was successful in completing its responsibilities as the observation tower remained open and staffed for most of the war years. As the war was winding down, the Tower went to a daytime schedule on October 5, 1943 and closed its door on December 2, 1943.

Here is an interesting account of one of the volunteers at the York Observation Post. This is from the records on file at the Old York Historical Society.

“Reverend Walter Harold Millinger (1896-1973) Minister at First Parish Church for 24 years. Millinger served in the navy in the closing months of World War I. He apparently wanted to join the army in World War II for in 1943 (at age forty-seven) and he went to U.S. Army Headquarters in Boston to have his heart examined by two doctors. They did not pass him. He remained on the home front as a member of the Draft Board, a member of the Home Guard (His rifle had a sight dated 1894!), an Air Raid warden, and he did more than his duty at the Observation Post at Roaring Rock, logging in at least 1500 hours of service.”

Photo credit: Courtesy of the Old York Historical Society. All rights reserved.

This photo was taken late in the life of the York Observation Tower.

No evidence of the tower exists to the present day.

Here are some newspaper clippings from the Portsmouth Herald with information about the Observation Post.

First clipping dated July 16, 1941; Second clipping dated December 10. 1941

Dimouts, Blackouts and Wardens

In early 1942, the American public was quite anxious regarding possible enemy air attacks. On the West coast the public was concerned about a Japanese attack along the Pacific coastline. In the eastern U.S. an air attack along the Atlantic coastline by the Germans was considered a real possibility. The citizens of York knew quite well that towns close to the Portsmouth Naval Shipyard faced a heightened chance of attack.

With these elevated threats, the U.S. Army established two lighting categories for homes, businesses and industry: dimouts and blackouts. The dimout standard called for reduced lighting with a focus on coastal areas. Most everyone in York was impacted by this new regulation put in place on May 16, 1942. Residents hung dimout shades or curtains over their windows each evening and throughout the night to minimize light that could be seen by enemy aircraft or submarines. Shop owners had to darken their storefront windows during evening operations. Cars traveling at night were required the prevent light from headlights from shining upward. Residents could use specially adapted headlight covers or, as most did, cover the top portion of their headlights with black electrical tape.

Compliance was not optional even though the dimout regulations left much to interpretation. There was some local pushback toward compliance, particularly with downtown Portsmouth merchants. Why? The local merchants wondered why they had to darken their storefront windows when the shipyard just across the river was ablaze with lights as workers were busy with 24 hour, around the clock construction. This issue was never fully resolved, even though attempts at a middle ground were sought.

And then there were blackouts drills. These left much less to interpretation. The regulations allowed no light leaks of any kind. The organizing and conducting of blackout drills was the Portsmouth Defense Council’s most important responsibility. Blackout drills were always pre-announced to the public. The shipyard did participate with some of the blackout drills.

In York, the signal to the public of an air raid was ten short blasts of the fire whistles atop the roof of both the York Village and York Beach Fire Departments.

York held its first blackout drill at the end of March, 1942. Local official declared the drill a huge success. Only one home in York Beach had a light visible in the cellar. Additionally, one person was spoken to because of smoking. From the York Village firehouse roof the only lights that were visible were from the bridge in Portsmouth and the beacons at Boon Island and Nubble Light. Those beacons were soon turned off for the duration of the War.

The Portsmouth Defense Council announced an air raid drill and blackout test for early May, 1942 for the towns of Kittery, Eliot, York, Wells and Ogunquit. This was one blackout drill of several that year for York and surrounding towns.

Here is a Portsmouth Herald newspaper alert dated May 22, 1942. This is the type of announcement which greatly increased the fears and anxiety of the general public. This announcement said there is “accurate” information from “police and Army authorities” that “foreign agents have landed on the coast of Maine.” This story turned out not be true, however, it was very alarming to local citizens and resulted in unnecessary mobilization of coastal observation teams. As the war continued, it was occasional false alerts like this which affected the morale Civilian Defense volunteers.

Here is an interesting Portsmouth Herald newspaper clipping from 7/20/1942. Other than the unique use of lipstick to dim the glow of the patrolman’s flashlight, this also indicates blackout drills were conducted in York Beach during the busy summer season. Granted, there were not as many tourists back in 1942, but I do know most hotels and rooming houses were open in the summer months throughout the war years. Of note, by late spring of 1942, regulations were established across Maine focused on hotels and apartment houses whereby they, “must submit to the municipal chairman of the local civilian defense council a statement indicating its plan for complying with blackout regulations.”

Henry Weaver, a resident of York Beach, was Chief of the Maine State Police during the war years. Here are two newspaper articles from the summer of 1942 concerning relaxed compliance with dimout regulations. As noted, he instructed his officers to “hale into court any willful violators” and to “patrol side roads that lead directly to the sea.” These Portsmouth Herald articles from July 1942 provide a good definition of what was expected of motorists to follow dimout regulations.

Air Raid Wardens

It’s time to talk about the important role of “Air Raid Wardens” sometimes referred to as “Neighborhood Wardens.”

These individuals were to a large degree the bridge between the country’s Civilian Defense organization and the general public living in homes across the nation.

Air raid wardens were designated as the first-responders in their neighborhood if bomb attacks did occur. The Handbook for Air Raid Wardens, published in 1941 by the U.S. Office of Civilian Defense, states that an air raid warden is “not a policeman, nor a firefighter, nor a doctor, although your duties are related to theirs. As an air raid warden, you have a unique position in American community life. It is a position of leadership and trust that demands an effort not less than your best.”

It was the duty of each warden to learn to know the people in his/her neighborhood, to ascertain how many people live in each house, whether there were invalids or deaf people who would be helpless in case of an air raid, etc. The wardens had a range of duties, such as advising local people on air raid precautions and monitoring night time ‘blackouts’ to ensure no artificial lights could be seen. These orders required all windows and doors to be covered at night with suitable material to prevent the escape of any light that might aid enemy aircraft in spotting a ground target. Air raid wardens would patrol their neighborhoods ensuring lights were dim.

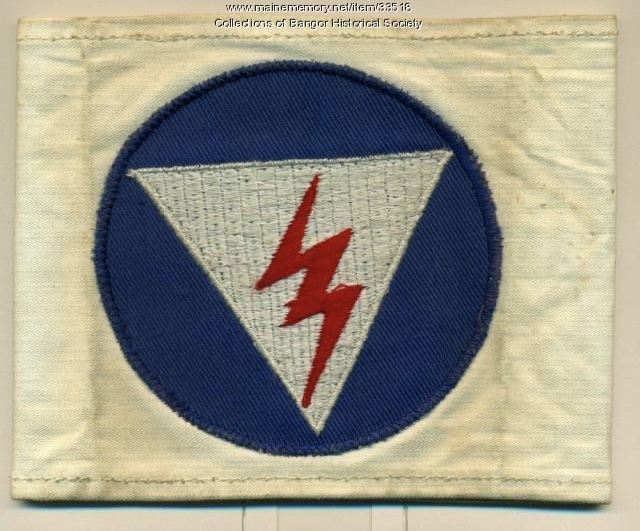

World War II air raid wardens were typically equipped with a steel helmet and arm patch (with the air raid warden’s blue circle with a triangular red and white striped insignia), police whistle, flashlight, translucent eye shade, small first aid kit, notebook and pencil, and a pad with report forms.

Typically wardens did not have enforcement duties. If violators did not feel it necessary to obey the rules and regulations of the nation at war, wardens would call law enforcement to enforce compliance with the rules. In York, a group of men were appointed war-time deputy sheriffs to assist the wardens in enforcement of the rules. Here is the announcement from the Portsmouth Herald dated January 23, 1942.

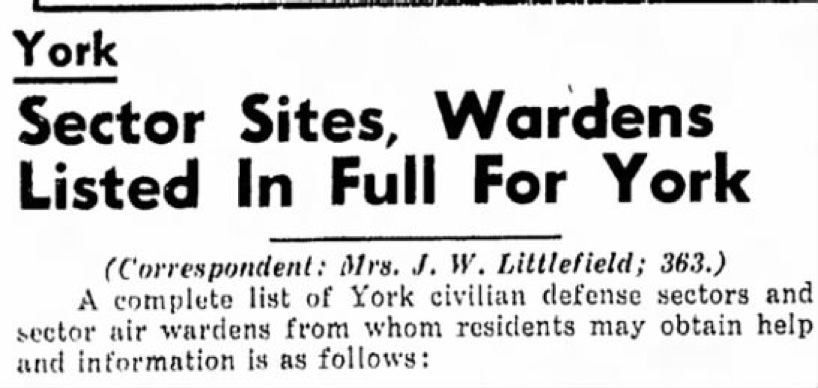

Here is a listing of the wardens in York and the neighborhood (sector) they covered. This was published in the Portsmouth Herald on July 14, 1942.

Sector Sites, Wardens Listed in Full for York

As the war progressed, dimout requirements were relaxed by the Army on May 31, 1943. For example, dimout now started one hour after sunset instead of 30 minutes, traffic lights no longer needed to be shielded to mere slits, and home owners could shield any three quarters of their windows rather than just the upper three quarters. By this point in 1943, with the shift of German military activities to focus on Europe and Russia and away from the U.S. mainland, the U.S. Army relaxed dim-out standards. Occasional blackout drills continued as communities continued with preparation for the possibility (though less likely) of air or submarine attacks.

Below is a photo showing a “Civil Defense Drill” from around 1943. Here the York Village Fire Department was carrying out its requirement to be prepared for any war-time situations. Additionally, the public was quite interested in viewing the fire department’s preparations.

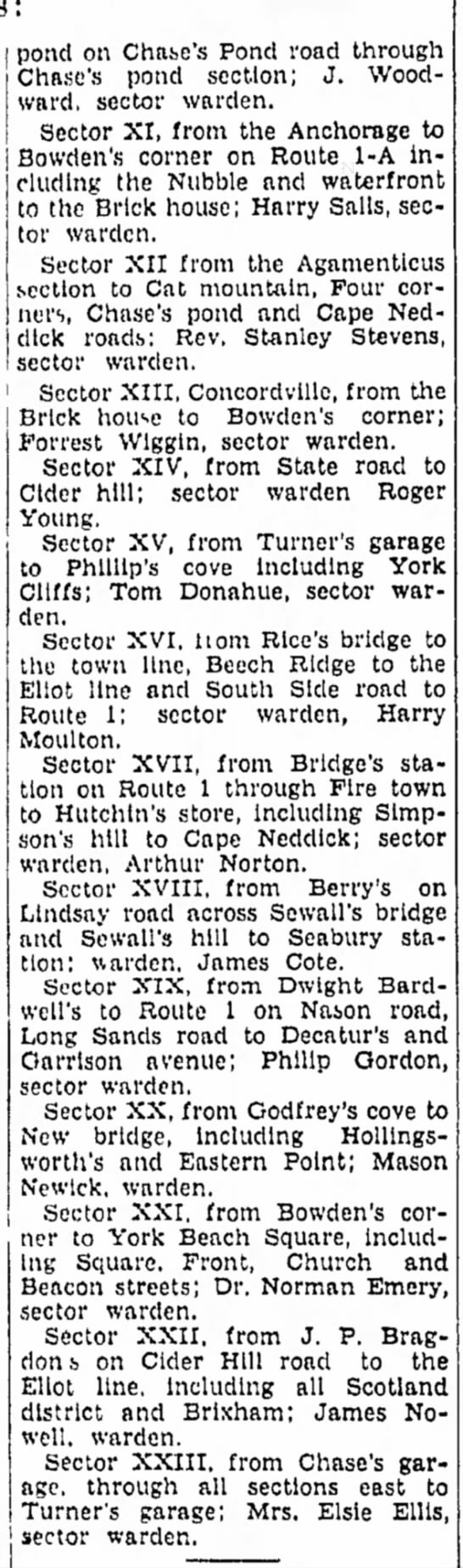

The announcement below of the suspension of dimout regulations along the Eastern U.S. coast was published in the Portsmouth Herald on October 28, 1943. This was welcomed news for seacoast Maine and New Hampshire, including the town of York.

On February 20, 1944 the Portsmouth Council of Defense went on a greatly reduced status. Lights could be turned back on and blackout shades removed from windows. The threat had subsided – the war was under control.

I found this advertisement in the Portsmouth Herald of November 5, 1943 interesting. Suspension of dimout requirements meant stores could now be open in the evenings, with “Saturday night shopping once again a pleasant task…” By this point, local citizens started to sense the end of the war was getting closer.

U.S. Coast Guard, U.S. Army

The following section describes six structures/facilities all located in York which were operated by the U.S. military during the War. No York citizens were stationed or volunteered at these locations.

During World War II the U.S. Coast Guard had responsibility to watch over the coastal areas of York.

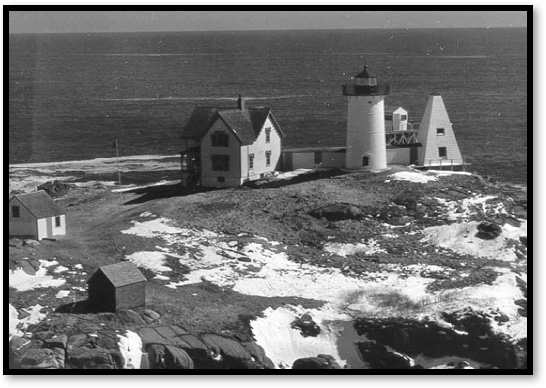

In addition to lighthouse operations, the Coast Guard also had responsibility for watchtowers on Boon Island and at the Nubble Lighthouse.

The Coast Guard manned a wooden watchtower located on Boon Island from 1941-1945. This was manned 24 hours a day, by a crew of ten, armed with rifles, watching for possible German spies or suspicious boats. The men had two day shore leave rotated every two weeks.

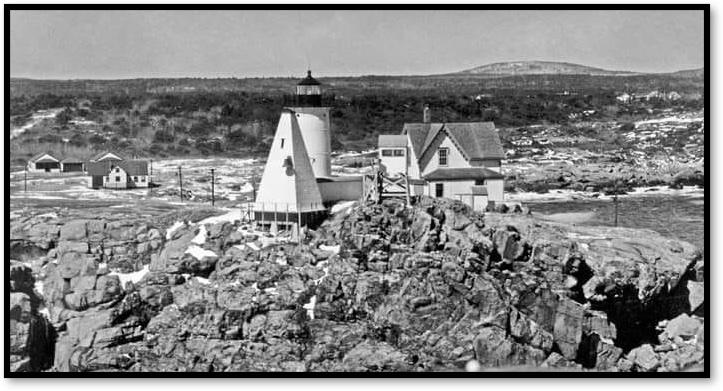

At Nubble Light a wooden watchtower was erected and manned by Coast Guard personnel during the War. You can see the watchtower in this photo (above) shown between the light tower and triangular bell tower. Below is another view of the watchtower from the rear of the lighthouse.

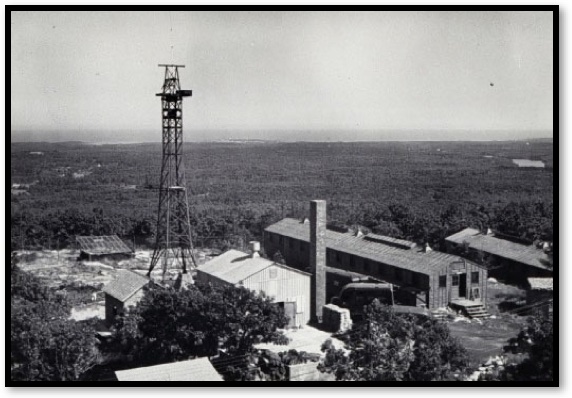

There was a radar installation with a steel framed tower located on top of Mt. Agamenticus in York during World War II. This was an anti-aircraft spotting station and early warning radar unit. Although not under the command of the Portsmouth Harbor Defense, the site was manned by 25 soldiers of the 551st Battalion, U.S. Army Signal Corp. The first soldiers to arrive lived in tents until barracks were built in 1942. Much of the complex was destroyed by fire in the winter of 1945 when fire equipment could not get to the summit due to heavy snow. The last military buildings here were demolished in the 1980’s. The only remaining evidence of this complex are the radar tower’s four concrete footings.

As mentioned earlier in this paper, starting in 1941, the Army Coast Artillery began installation of new gun batteries at Fort Dearborn in Rye, NH to house large scale guns to protect the mouth of the Piscataqua River and the Portsmouth Naval Shipyard. An additional battery for large guns was planned at Fort Foster in Kittery but construction was halted in 1944 due to the war coming to an end. To support the operations of these large guns, the Army Corp of Engineers erected thirteen “fire control towers” from Cape Ann, MA to Kennebunkport, ME. Measurements gathered at the towers by Army Coast Artillery soldiers were sent via a private phone network to Fort Dearborn where the information about the specific target at sea was consolidated from at least two towers with a method called triangulation to determine the precise location of the enemy ship. In turn this information was sent to the gun batteries so the guns could be positioned correctly during firing to successfully hit the enemy target. The range for the Fort Dearborn guns was from 17 to 25 miles.

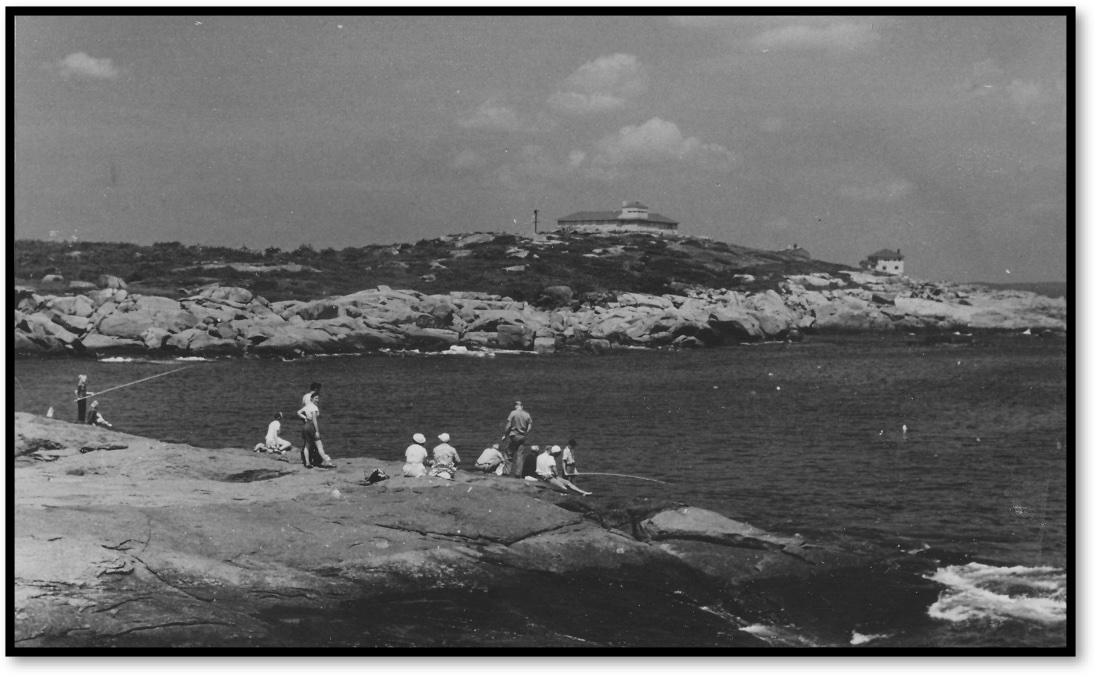

In York, there were three of these fire control towers: one at Bald Head Cliff, one on Nubble Point, and the last one just south of Godfreys Cove. These towers were built from 1942 to 1943. They were built with reinforced concrete to withstand any possible attacks from the enemy. They all included a barracks to house the Army Coast Artillery soldiers.

Above is a photo taken in 1951 of the Army Coast Artillery tower and barracks located on a high location at the end of Nubble Point. Of the three World War II fire control towers in York, this is the only one to survive to the present day, though greatly reduced in size and modified. The building and 1.4 acres of land was considered surplus property and sold by the government in 1946 for $1. The building was then modified into a private home.

The tower and barracks at Bald Head Cliff was demolished in 1964 to make way for Cliff House expansion. The tower located at Godfreys Cove (officially called the “Seal Head Point Station”) was demolished in 1980 to make way for a private home.

Coast Guard Auxiliary and Coastal Patrols

In 1939 and later renamed in 1941, the Coast Guard created the Coast Guard Auxiliary. This division of the Coast Guard was charged with promoting safety and conducting safety and security patrols in support of and supplementing active duty Coast Guardsmen. The Coast Guard Auxiliary was a non-military organization performing services on a volunteer basis. This is where the citizens of York entered the picture to assist the military.

During World War II the Coast Guard had three patrol divisions in York under their supervision – the Cape Neddick Beach Patrol (this included Long Sands and Short Sands), Godfrey’s Cove Beach Patrol, and York Harbor Patrol. The Coast Guard had a patrol boat assigned to them to assist with this local activity. To supplement active duty Coast Guardsmen, the Coast Guard Command recruited local, volunteers to staff the Coast Guard Auxiliary to handle the various beach patrols in York. Any man below an A-1 draft classification was eligible for the beach patrol duties. In addition, local individuals at least 18 years of age who owned a boat of 16’ or more could join the Auxiliary and assist with ocean patrols. As available, the Coast Guard would loan radio equipment to these boat owners and provide them with instructions for use.

Within these parameters, the Coast Guard was able to fill vacancies with the necessary volunteers for beach and ocean patrols in York throughout the war years. After the war ended in 1945, there were no reports of enemy landings or German U-boat activities reported by these beach patrol units.

I can’t imagine the beach patrols were an exciting assignment. Patrols were conducted year round, at night, in good and bad weather conditions. As noted in this quote from material preserved at the Old York Historical Society, Eddie Cooper and George Gilcrest, both from York, were assigned to beach patrols. They mentioned, “duties at York during WWII were to walk the length of Long Beach, from York Harbor to York Beach, ‘clocking in’ at a time clock located at the Fairmont Hotel, and returning to the Coast Guard Building (barn) on York Street near the northern intersection with Norwood Farms Road. This observation took place at night, year round. Sometimes the snow was very deep at York Beach, especially when walking. It is about 6 miles round trip.”

Rationing

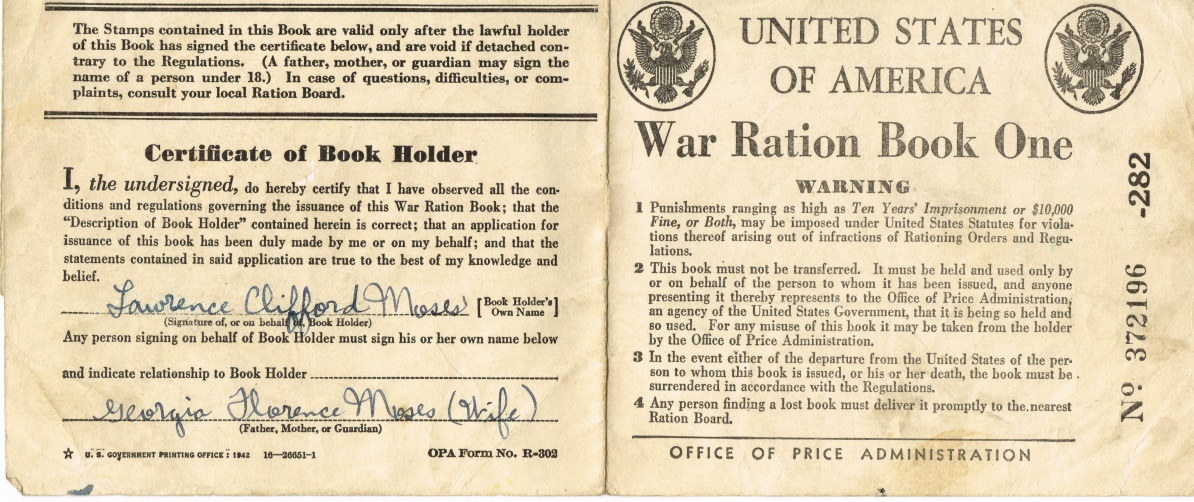

The last category to be discussed under the “defense” category is rationing. Of the activities discussed so far, some required mandatory participation and others were voluntary. The activity of rationing was a mandatory war time activity.

The following narrative includes excerpts from the National World War II Museum in Louisiana.

World War II put a heavy burden on US supplies of basic materials like food, shoes, metal, paper, and rubber. The Army and Navy were growing, as was the nation’s effort to aid its allies overseas. Civilians still needed these materials for consumer goods as well. To meet this surging demand, the federal government took steps to conserve crucial supplies, including establishing a rationing system that impacted virtually every family in the United States.

Rationing involved setting limits on purchasing certain high-demand items. The government issued a number of “points” to each person, even babies, which had to be turned in along with money to purchase goods made with restricted items. These points came in the form of stamps that were distributed to citizens in books throughout the war. The Office of Price Administration (OPA) was in charge of this program, but it relied heavily on volunteers to hand out the ration books explain the system to consumers and merchants. By the end of the war, there were about 5,600 local rationing boards across the country.

Tires were the first product to be rationed starting in January 1942, just weeks after the attack on Pearl Harbor. Everyday consumers could no longer buy new tires; they could only have their existing tires patched or have treads replaced. Doctors, nurses, and fire and police personnel could purchase new tires, as could the owners of buses, certain delivery trucks, but they had to apply at their local rationing board for approval. Personal automobiles met a similar fate in February 1942 as auto manufacturers converted their factories to produce jeeps and ambulances and tanks. Gasoline was rationed starting in May of that year. The government also began rationing foods in May 1942, starting with sugar. Americans received their first ration cards in the same month. Coffee was added to the list that November, followed by meats, fats, canned fish, cheese, and canned milk by March of 1943. Of note, fresh fruits and vegetables were never rationed. Another food which was not rationed was fish. The citizens of York were fortunate to have a supply of ocean fish and shell fish. Locally, this eased the inconvenience of a limited meat supply.

Americans were issued a series of ration books during the war. The ration books contained removable stamps good for certain rationed items, like sugar, meat, cooking oil, and canned goods. A person could not buy a rationed item without also giving the grocer the right ration stamp. Once a person’s ration stamps were used up for a month, they couldn’t buy any more of that type of item. Restaurants instituted meatless menus on certain days to help conserve the nation’s meat supply. Macaroni and cheese became a nationwide sensation because it was cheap, filling, and required very few ration points. Kraft sold 50 million boxes of its macaroni and cheese product during the war. The system wasn’t perfect. Black market trading in everything from tires to meat plagued the nation, resulting in a steady stream of hearings and even arrests for merchants and consumers who skirted the law.

Americans learned, as they did during the Great Depression, to do without. Sacrificing certain items during the war became the norm for most Americans. It was considered a common good for the war effort, and it affected every American household. As World War II came to a close in 1945, so did the government’s rationing program. By the end of that year, sugar was the only commodity still being rationed. That restriction finally ended in June 1947. Plenty of other goods remained in short supply for months after the war, thanks to years of pent-up demand.

Section 2 – Civilian Defense Voluntary Services

After the December 7, 1941 Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, there was a shift in the way Americans thought of volunteerism. No longer was volunteerism only a matter of charity. It was now, in the minds of the people, vital to national survival. Federal, state, and local governments confirmed this view by creating organizations and programs which provided all Americans with the opportunity to volunteer and aid the war effort.

Following is a discussion of a number of volunteer activities which York citizens and citizens in surrounding communities participated throughout the war years. Among the most popular volunteer activities for York were the categories of Victory Gardens, Scrap and Salvage Drives, War Bonds and Stamps, and Medical / Red Cross.

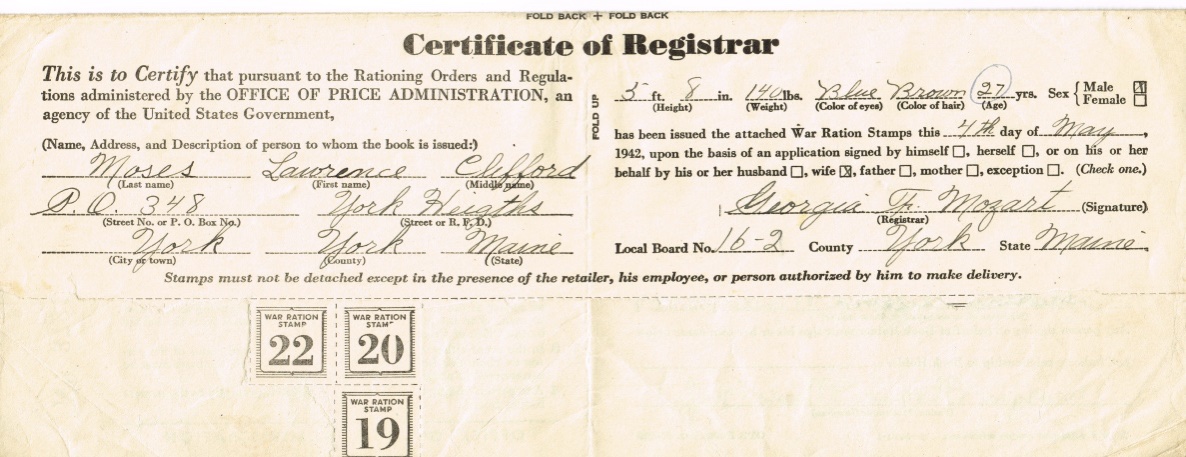

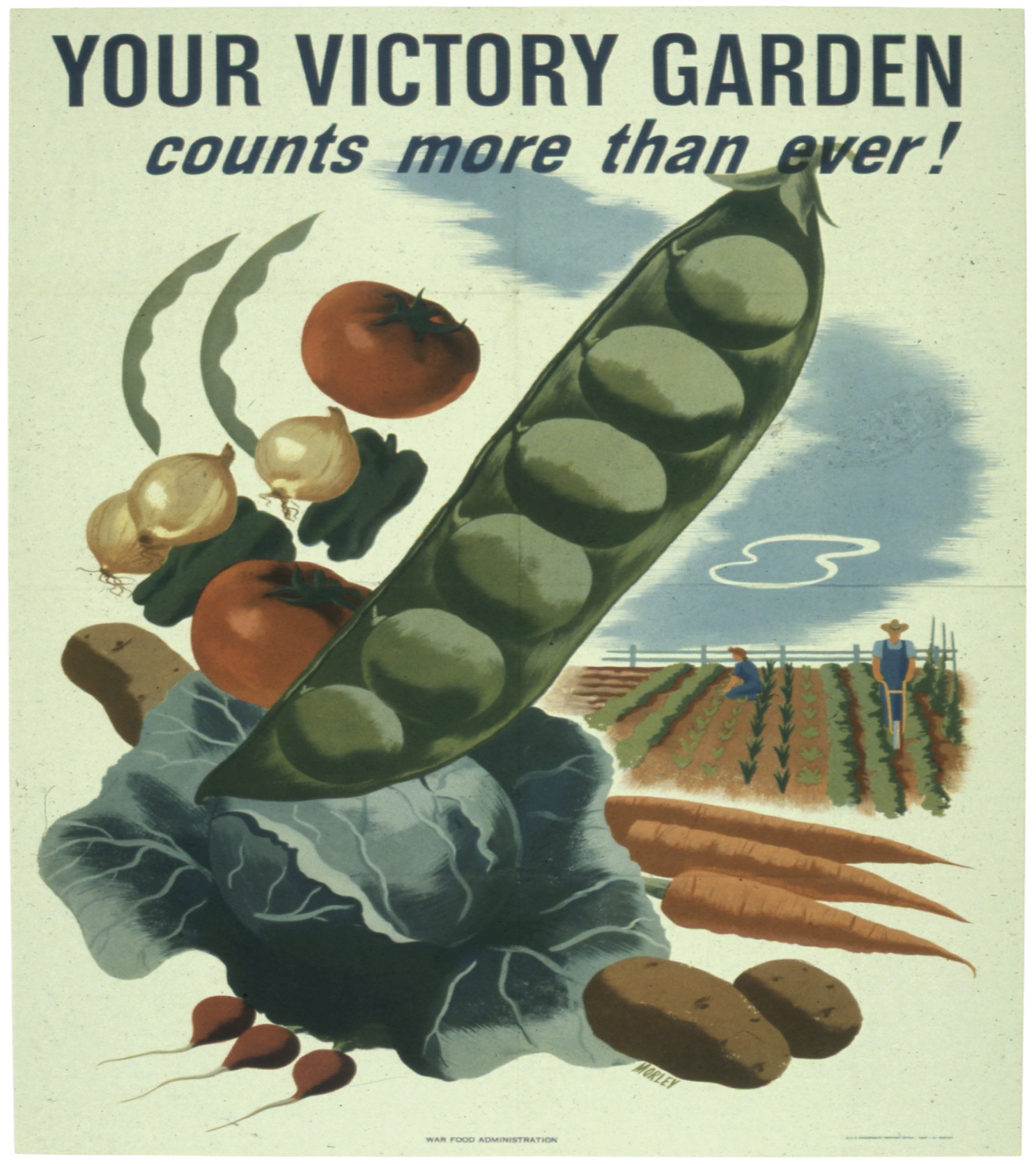

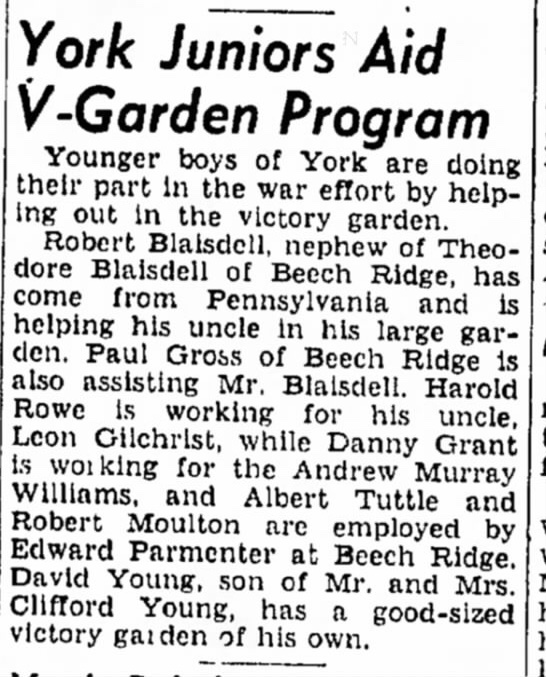

Victory Gardens

Victory gardens, mostly consisting of fruits and vegetables, were widely planted by individuals at home or in a common neighborhood setting during World War II. The gardens, used along with rationing cards and stamps, helped to prevent food shortages and freed up commercial crops to feed soldiers. Planting a Victory Garden boosted morale by providing a way for folks at home to do their part in the war effort.

Commercial crops were diverted to the military overseas while transportation was redirected towards moving troops and munitions instead of food. With the introduction of food rationing in the United States in the spring of 1942, Americans had an even greater incentive to grow their own food.

The Victory Garden campaign served as a successful means of expressing patriotism, safeguarding against food shortages on the home front, and easing the burden on the commercial farmers. In 1942, roughly 15 million families planted victory gardens; by 1944, an estimated 20 million victory gardens produced roughly 8 million tons of food—which was the equivalent of more than 40 percent of all the fresh fruits and vegetables consumed in the United States.

Here in York, as well as surrounding towns, there were talks and educational presentations with instructions of best practices for home gardens. In my present day discussions with individuals who lived during the war years as a young child, one of their clearest and fondness memories was working with their parents or grandparents in planting and harvesting home gardens. These garden activities helped to unite families as they contributed together in a cause helping America to win the war.

My parents, who lived in Kittery, owned a field where they planted a large crop of strawberries in 1942 and 1943. Beyond enjoying the fruit for themselves, they contributed strawberries to many and sold some at local markets. Here’s a photo of my mother from 1943 working in the Prince family Victory Garden.

Scrap and Salvage Drives

Many York citizens were voluntary participants in scrap and salvage drives throughout the war years. These drives were one of the most important activities of the Portsmouth Defense Council.

During World War II, the United States government encouraged the American people to participate in scrap drives. Citizens were asked to turn over to the government items that would prove to be useful in the war effort. These items included products made out of rubber and most types of metal, kitchen fat, newspapers, and rags, among other items. The government then had various industries recycle these products into weapons and other items necessary for the war effort, ensuring that United States soldiers had the items necessary to defeat the country’s enemies.

For York, many drives were organized and conducted locally. This was the same for other towns in the surrounding area. Some drives were National in scope. President Roosevelt initiated a scrap rubber drive from June 16 to June 30, 1942. People brought in old or excess tires, raincoats, hot water bottles, boots and floor mats. Citizens participated by taking scrap rubber to their nearest gasoline station. For southern Maine and seacoast New Hampshire, the scrap rubber was hauled to regional collection sites in Portsmouth. Participants were given a penny a pound for scrap rubber. Although 450,000 tons of scrap rubber was collected nationally, much used rubber was found to be of poor quality.

Another drive happened early in the war when aluminum was in short supply. A call went out to housewives to gather up any surplus pots and pans. Nationally, women went through their kitchens and donated 70,000 tons of aluminum.

Another drive which was asked of the women of America was to take kitchen oils and grease to their local grocery market. Once collected and consolidated, glycerin was extracted for mixing with black powder needed for artillery shells. Before the war, the fats and oils from which glycerin was made were imported from the Asia Pacific region which was now under Japanese control following the beginning of the war. The US and Allied forces had a tremendous need for glycerin for their weapons which was solved by housewives here in York and across America.

Scrap iron, tin, copper and other metals were gathered locally and across America as a valuable resource and raw material. Here in York, the Boy Scouts took an active role in gathering scrap metal from neighborhoods. By recycling unused or unwanted metal, the government could build ships, airplanes and other equipment needed to win the war.

The next step in the process was to consolidate the scrap in Portsmouth, where it was loaded on train freight cars to be taken elsewhere for processing.

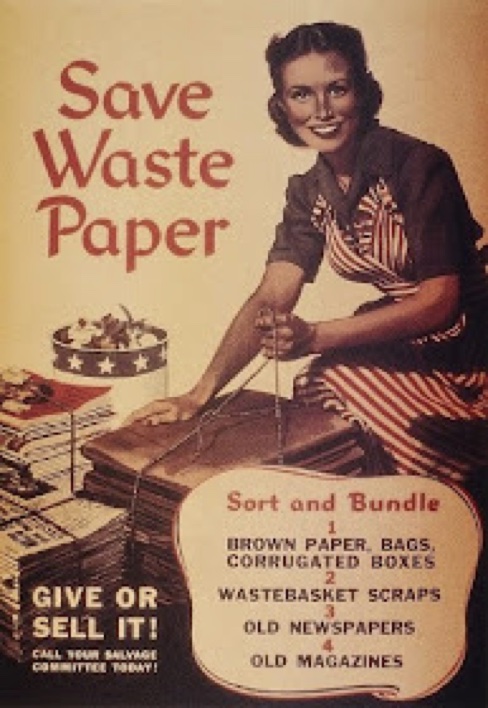

Much the same process was used locally for paper drives. Locally paper was mostly loaded on to ships docked at Market Street in Portsmouth, site of the present day supply of road salt. The need for paper increased during the war. The military’s love for paperwork could be blamed, but the military also used lots of paper packaging for supplies. On the civilian side, paper packaging had replaced tin for many products.

A National paper drive in mid-1942 brought in so much paper that mills were inundated and actually called for a stop. However, by 1944 an acute paper shortage existed and paper drives became necessary once again. The children of America stepped up. Locally, schools, Boy Scouts and Girl Scouts organized paper drives, often coordinated with tin can drives.

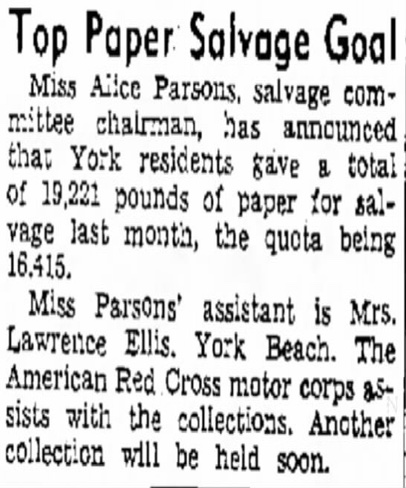

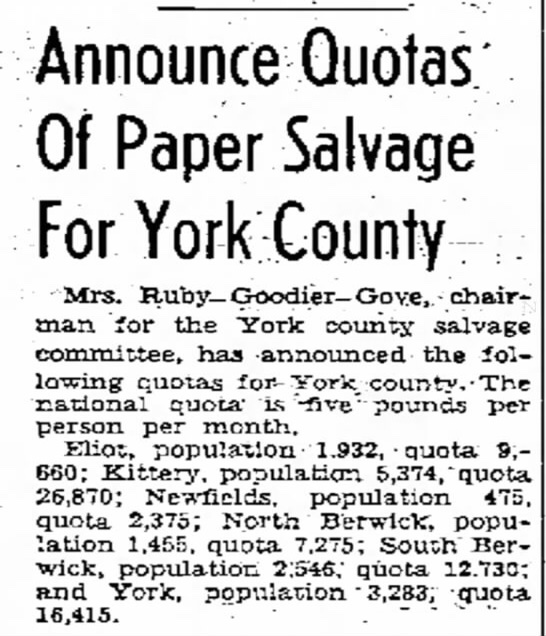

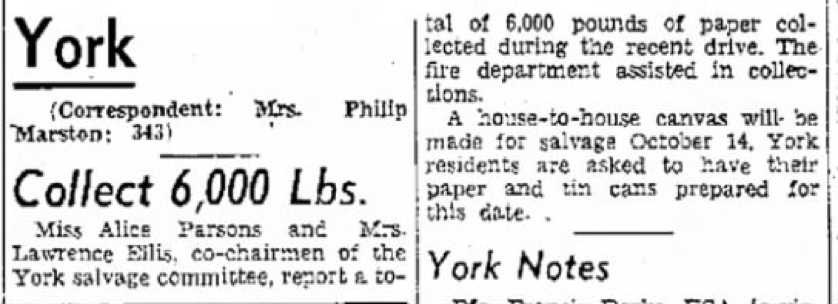

Below are Portsmouth Herald articles from July 1944 showing the quotas and goals for paper salvage.

July 19, 1944 indicates York exceeded its goal for June 1944

For York, the target for July 1944 drive was collection of 16,415 pounds of paper.

Above are the results for a paper drive in York in September 1944. You’ll note, the fire department assisted with collection. By now, fire department training for possible air raids was significantly less, thus, the fire department stepped up to volunteer for paper drives.

Scrap and salvage drives were a vital part of the American war effort. While not all scrap materials proved useful, many did and provided a small but significant source of material. Most importantly, these drives galvanized the Home Front and made each individual, even children, feel like a crucial part of the war effort.

to encourage citizens to save and recycle paper. Credit: National Archives, Washington DC

War Bonds and Savings Stamps

During WWII the United States issued War Bonds which were at first labeled Defense Bonds. These bonds were sold throughout the U.S. to help the government raise money to help finance the United States’ war effort. There was a nationwide effort to advertise the bonds, ranging from sports events to radio show promotions. The purchase of the bonds was largely linked to patriotism and to people’s feeling of “doing their part” in the war.

Congressional Research Service records indicate that World War II cost the United States the staggering equivalent of roughly $3.9 trillion in today’s dollars. In 1945, the war’s last year, defense spending comprised about 40% of gross domestic product (GDP)

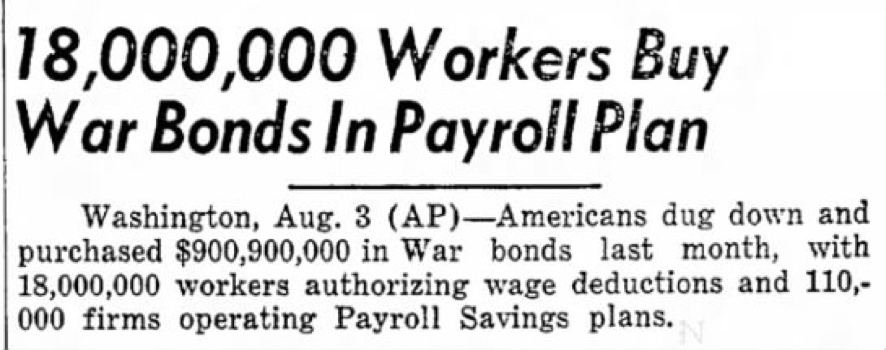

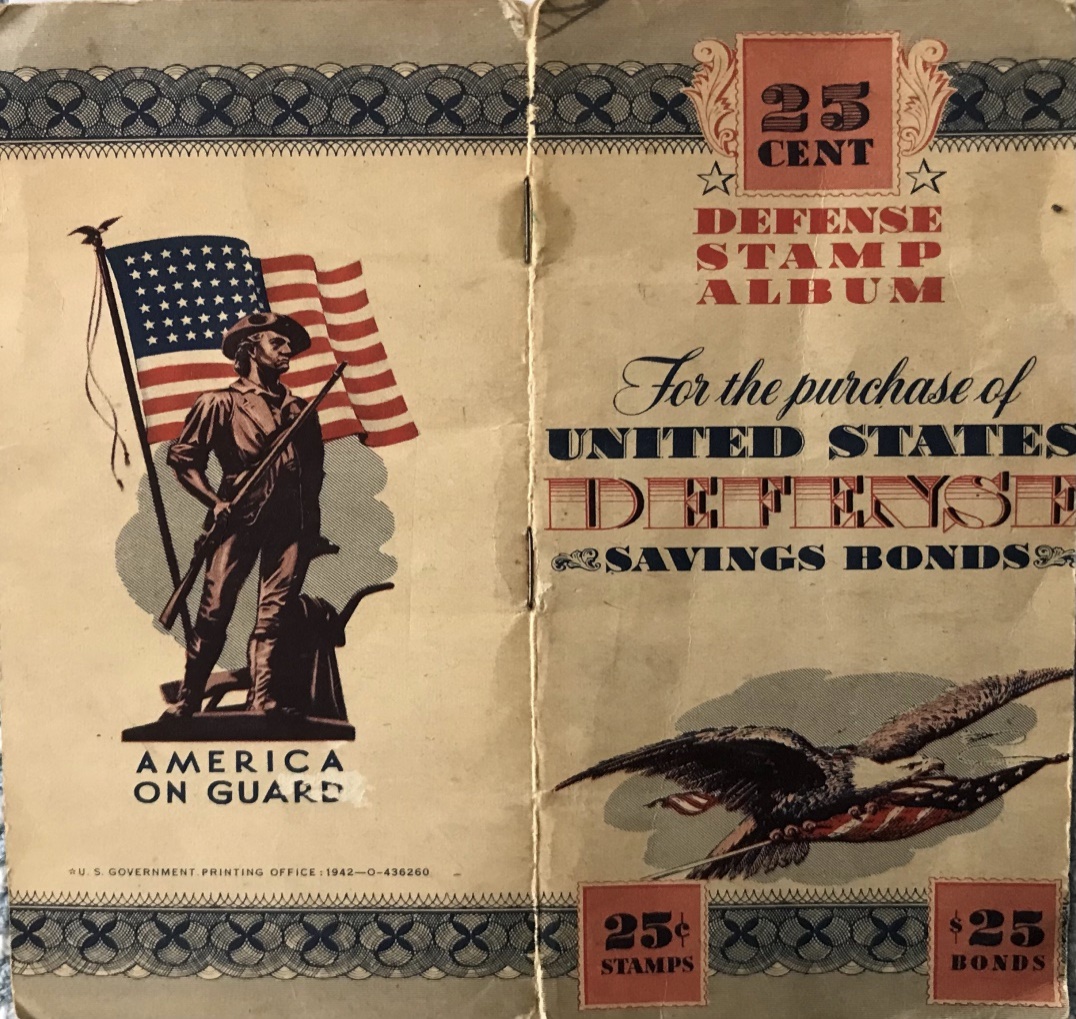

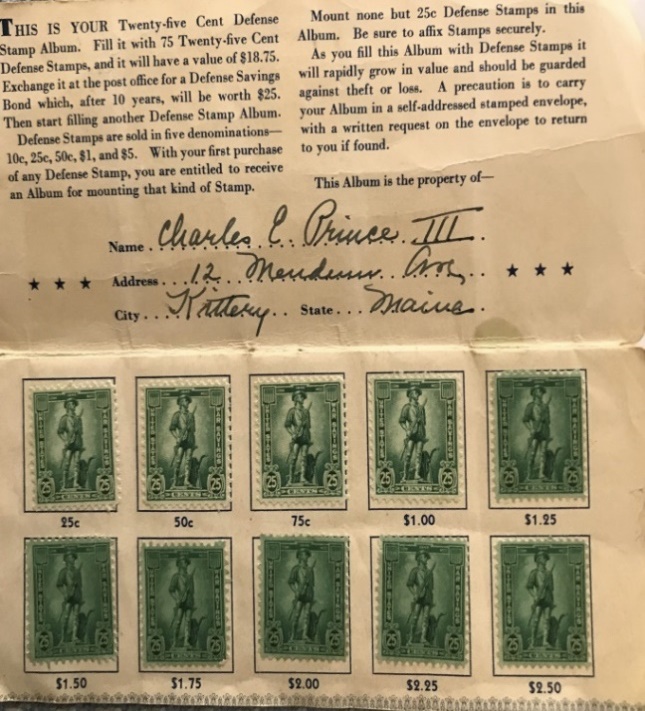

Bond drive tactics and strategy were very common during World War II. Non-negotiable Series E “Defense Bonds” were introduced in $25, $50, and $1,000 denominations. The $25 bonds became the most publicized and most popular, selling for $18.75 and maturing over a ten-year period to pay the bondholder $25. Beginning in 1942, these War Bonds could be purchased on an installment plan through payroll deductions at the work place. And since one wartime slogan was “We’re all in this together,” an installment plan was even established for school children who could buy twenty-five cent war stamps to paste into a book until they saved the $18.75 needed to buy a $25 war bond.

Above is a report of national sales of war bonds for July 1942. The war bonds sold from 1941 – 1945 in the US helped the government raise about $185 billion. War Bonds were bought by over 84 million Americans.

Here in York, many citizens, families and organizations participated in buying War Bonds. One example was the First Parish Church in York Village which invested in War Bonds for the church’s Restoration Fund.

Another example of one family’s participation was my parents. My dad worked on the Navy Yard and had money withheld from his paychecks to buy a bond each month. Also, when my brother was born in 1944, my parents opened a defense stamp album for him. Thereafter, each week, they would purchase a twenty-five cent saving stamp and stuck it in the book. The goal was to purchase 75 stamps which would equal $18.75, which they would then convert into a $25.00 war bond for my brother. World War II then ended on September 2, 1945 with the surrender of Japan. This was 64 weeks after my parents started my brother’s savings plan. They chose to hold on to the book, though incomplete, with $16.00 worth of stamps and keep it as a memory of the war. Fortunately, our family still has the book which I photographed below and used in the writing of this report in 2022. By the way, the $16.00 in this book is still recognized as a debt of the United States and could be turned in anytime at a post office for collection.

Medical / Red Cross

During WWII, York women made contributions to the war effort through various avenues including the medical field under the direction of the American Red Cross. The goal of these women was to volunteer as nurses or nurse’s aides. Through the Volunteer Nurse’s Aides Corps, women provided aid to overworked nurses. Women also provided medical aid through different means such as the American Red Cross Motor Corps. This was a program, mostly comprised of women, where volunteers transported supplies, injured personnel, and volunteers to other hospitals. York’s Red Cross Motor Corp assisted with transportation of citizens assisting in the war effort around York throughout the war years. As mentioned earlier, they even assisted with the collection of paper gathered in York on paper drives.

For the whole duration of the war, the Red Cross Nurse Service enrolled nationally over 200,000 people and certified half of these people to the military service. These nurses served on front lines as well as in overseas hospitals caring for injured soldiers and aiding in the rehabilitation of service members. Nurses on the home front had similar duties but assumed even more responsibility in order to replace the work gap caused by the shortage of doctors and other medical staff during the war.

The photo below and newspaper article records the Red Cross Volunteer Nurse’s Aides first graduating class at York Hospital, April 1943. This was the first nurse’s aide class to be sponsored by the York County Chapter of the American Red Cross of which the York Red Cross was a branch.

York’s branch of the Red Cross coordinated several blood drives during the war years. The volunteers for the Red Cross also conducted many instructional courses for York citizens. Topics included, home nutrition, home nursing, rolling bandages, and first aid.

Many of these educational classes were held in Jefferds’ Tavern on York Street. This building, originally built in 1760, was moved from Wells to York Street in York in 1941 under the supervision and support of Miss Elizabeth Perkins. Her participation in organizations such as Historic Landmarks and the Garden Club was how Miss Perkins expressed her patriotism. During the war years Jefferds’ Tavern became the central headquarters for Allied support. The building, after being taken apart and moved piece by piece to York and then reassembled, had two rooms converted for classroom training with the remainder of the building used for collection of salvaged newspapers and a place to receive boxes of clothes and supplies to be sent to the US armed forces and allied nations. In early 1945 York participated in the United Nations Clothing Drive which was conducted by the York’s Women League, the Girl Scouts and postmasters. All clothing was gathered at Jefferds’ Tavern.

being delivered to Jefferds’ Tavern during World War II.

Note sign on building, “Aid to All Allies.” Photo credit: Courtesy of Old York Historical Society. Elizabeth B. Perkins Collection. All rights reserved.

Much of the clothes had to be repaired or mended before domestic or overseas shipment. That work was carried out by elderly women from various churches, women groups and ad hoc home gatherings in Kittery and York. These elderly women were otherwise not able to participate in scrap drives or neighborhood watches, but they certainly were handy with needles, yarn and thread. These groups were active throughout the war years, typically meeting at homes to darn old socks and repair damaged clothing.

This group of Kittery ladies, pictured below, met frequently during the war years to mend and repair clothing which was sent to the York County American Red Cross in Saco prior to shipment overseas to U.S. military troops and Allied countries. Of note, the lady on the left taking a tally is my grandmother, Edna Prince. She participated in this activity from 1941-1945 never missing a meeting.

Last but not least, the Girl Scouts collected buttons throughout town to assist with the repairs of the clothing being shipped to the Red Cross. From the elderly to the very young, everyone did their part to assist with the war effort. It’s not surprising the Allies won the War!

Tom Prince – York, Maine